Introduction

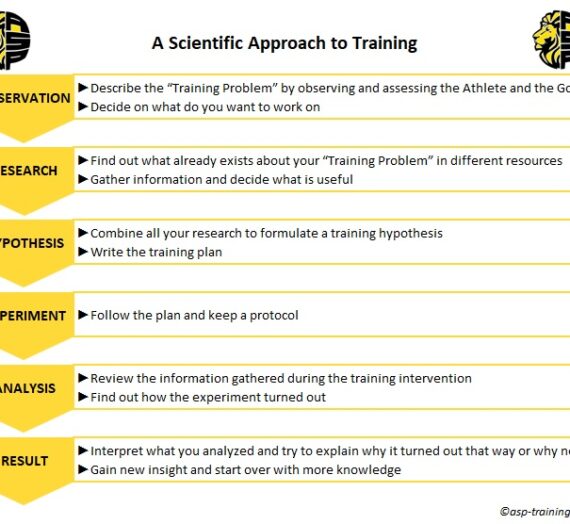

As coaches we strive to find and prescribe the right training to optimally enhance our athlete’s performance. Sometimes we commit the fallacy to think that we can control the whole process when in reality this is not possible: Why? Because the “training problem” is complex not simple. Simple problems have one single path leading to the solution whereas complex problems have many paths to many possible solutions. Complex systems cannot be controlled but must be managed instead. To better deal with complexity it helps to create models that somehow describe the problem and processes and feedback to find opportunities to manipulate the system. All models are wrong, but some are very useful.

Training and competition consist of many variables that all combined create a load on an athlete. One of our tasks as Strength and Conditioning coaches is to manage the load and to find a way to optimally stimulate adaptations while also keeping in mind that the body needs some time to recover from a given load. The proposed model of training load management was created as a short summary of a one-week seminar about the topic of load management at the ISNEP in Paris as part of the ESC2 Course I am currently undergoing. I tried to integrate inputs of the different lecturers, guest speakers and different scientists and trainers working at INSEP.

Having a basic model

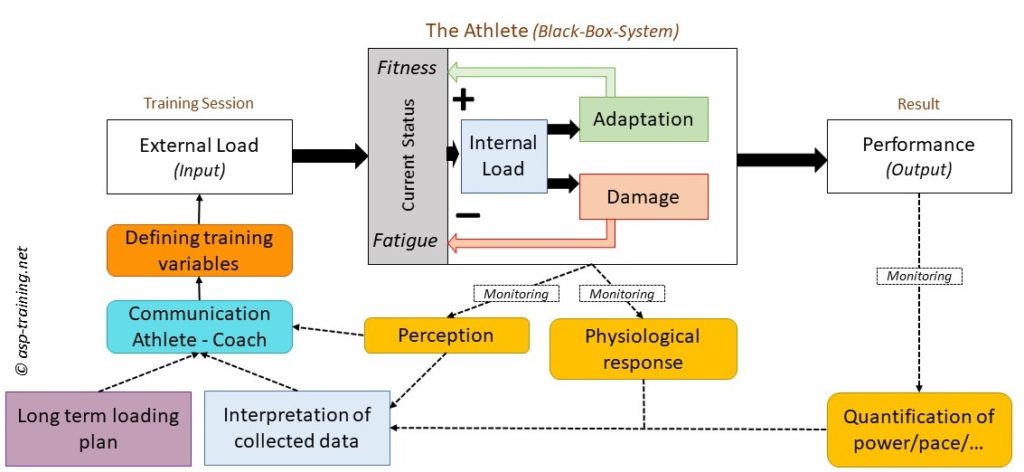

The model is built with the athlete in the center of attention. The athlete is treated as a black box, because we cannot describe exactly what effect any given input (or load) has on the whole system. The Athlete is why we are dealing with a complex problem in the first place. Inside the “Black Box” there are a big number of different processes and interactions between processes etc. The best we can do is to do research and to create models to describe the system we call “Athlete”

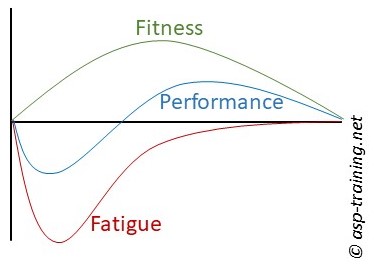

The Fitness/Fatigue Model describes the athlete’s performance as the sum of two different factors: Fitness and Fatigue. On one side, a training session stimulates adaptations in the body that increases the potential of performance. Fitness is used as an umbrella term to describe everything that allows performance to be expressed. The same training session also causes damages to the system that hinder performance, factors we sum up as Fatigue. The increase of Fatigue as a training after effect is acute, the increase in Fitness on the other hand is delayed. That’s why the performance is lowered right after a training session but improved once the fatigue is gone. Both, Fitness and Fatigue are present at the same time in the system, and the sum of both decides how a training input or a competition is handled by the system and what will be the performance result to an input to the system. The essence of managing training load is to try to estimate where both curves are at all the time and to try to anticipate where they are leading to find the optimal measure for an athlete at any given moment. Both, Fitness and Fatigue have many different components, physiological ones as well as psychological ones that are differently important in different sports: You see where I am going… It’s impossible to predict the exact outcome of a training session, and we must get used to that. Should we give up and stop coaching? I don’t think so… First of all, just because we don’t know what exactly will happen, we still have some solid theories about what most probably will work under given circumstances and what not: We have evidence based training methods as well as anecdotal knowledge and experiences to base our decisions on. Our prediction will not be exact, but hopefully damn close to it! The better we know how our athletes are, physically and mentally, the more probably we chose a good practice and/or see alarm signs when the athletes are at risk of injury and overtraining.

For each training session coaches should have an idea about what adaptation they want to trigger with the unit of training. This determines the training session the athletes must perform and it is the “input” to the model: With the help of controlled experiments and statistics (aka science) evidence based training models have been created that help us to maximize the chance to target the “right” adaptations. These models are the textbook training methods like the widespread: “Do 3×8-12 Reps of curls at moderate resistance for hypertrophy gains in the biceps”. The better our understanding of the individual athlete, the better our choice of the training method and load will be, that’s why individualized training programs are superior to cookie cutter programs. Cookie cutter programs generally work with a lot of the people to some extent, but the higher the profile of an athlete is, the greater the chance is that a “generic” training session does not yield the results we wish for anymore. That’s why the more advanced an athlete is in his sport, the more individual and specific the training often has to be. When knowledge of training methods and demands of the sport meet understanding the status and needs of an individual athlete, magic happens!

Without going into too much detail about the exact content of a training session, every session has a certain volume (how much/long) and intensity (how hard): These are the very basic variables, but they are essential when it comes down to prescribe training and training load. Sometimes these training variables can be given very exact (e.g. for a powerlifter, a coach can prescribe an exact number of Reps at given weight for every exercise of the session) while in other cases this is more difficult. Team Sport practices for example are “chaotic” in their essence and the prescription has to be more variable. Still it’s possible to plan a training session to e.g. be intensive or not and for how long the session will run etc. Intensity limits volume and in their combination, they create Fatigue: As training is a process and involves multiple sessions over a certain time, a third very important variable comes into play: Frequency (how often). All three variables are interconnected and have to be carefully decided.

To complete the model: An external load (the prescribed training session) applied on the System will result in a certain performance output: Because we cannot exactly predict what this output will be, we have to find a way to quantify or monitor it: In this model the term performance is used to describe the “hard facts” or external work in a physical way e.g. a certain pace for a marathon runner. Aside the performance output the system responds also in other ways to an input/stimulus. We have a physiological response that can give insight in how the biological system is working to get this physical work done. This can be e.g. Heart Rate or lactate accumulation among other variables. The third thing, more difficult to measure directly, is the psychological response of the system (perception) and is obtained by talking with the athletes or monitor their wellness. Stephen Seiler called this the P^3, the Trinity of Athlete monitoring: Pace/Power, Physiology and Perception.

The Model as a whole per se is a feedback loop, that tries to capture the most important factors to optimize itself: What makes this model complex and limits it is, that as coaches we deal with people and not robots. To Draw a conclusion, if training is going the right way, we have to gather some data and interpreted it, put into context of the actual training phase and checked with the athlete to adjust for the next training. To some extent we can “guess” the outcome, but we have to veryfy with looking at the actual training outcome.

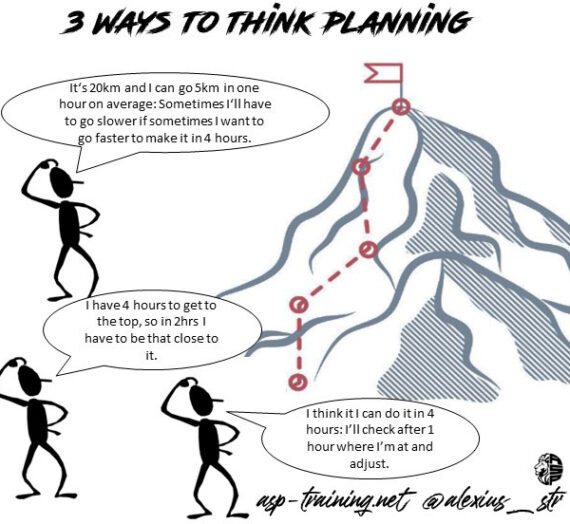

Load management happens on many levels: Form deciding sets and reps of single “exercises” to planning complete sessions, managing training weeks and cycles, and outlining a yearly or even career plan. Progress is the accumulation of thousands of little improvements, sometimes almost invisible, over all the training sessions: Sometimes it gets easy to get lost in the details of a single training session and forget about the big picture. Yes, every training session counts because of its, even if small, performance gain potential that, done consistently, leads to big improvement in training and performance over time. Paradoxically, sometimes having a bad training session will not count that much if overall, we are moving to the right direction. Now we are really getting to the crux of the matter of managing training load: Are we moving to the right direction in the current session, week, cycle? (Sidenote: To know if we are moving to the right direction, we need to have a direction in the first place; that’s why having a plan is so important)

To find out if our performance is improving over time and how the status of athlete-system currently is, we must measure and track some variables: We need some data to base our decisions on; that’s when monitoring comes into play to provide us with that data. What exactly we should track is difficult to generalize as its mostly dependent of the characteristics of the sport:

Of course, every part of this model could be outlined in greater detail, but for now it is enough to get the “big picture”. As every model it is incomplete and simplified but a good start to work with and adapt it to your needs.

In Pt. II I will try to get more into the practical side of managing training load, so see you around…

Alex