From Theory to practice I – Keep it simple

During the INSEP lectures many scientists and coaches have shared insight in their work and have given practical hints how to implement ideas from science and practice. My personal biggest take away message was to keep it as simple as possible and only as detailed as necessary: The more data one collects, the more has to be processed to draw a conclusion: Most practitioners neither have the budget nor the knowledge or man force to process all the data in a reasonable time span to really support coaching. Technology has made it possible to track many things like GPS, LPS, Heart Rate Zones, Accelerations etc; the term “Big Data” is out in every existing field of business nowadays but just because one can measure all the things it doesn’t mean it’s necessary. Technology is not always the solution and as a coach it makes only sense to measure what one can use after. Integrating a scientific approach in training does not automatically mean, that a coach should track everything possible the same way as a researcher maybe does. For me, using a scientific approach in training means that as a coach I adopt the scientific thinking: I create a hypothesis based on the current knowledge (e.g. training method XY will improve my athletes vertical jump), test the hypothesis with an experiment (e.g. doing the training cycle) and compare the pre and post intervention results to draw conclusions. Integrating science means to use the work and help of scientists to find valid and reliable methods to design and review the whole training process to be as effective and efficient as possible. Of course, gathering every possible data, potentially can give you a better image of an athlete, but if you can’t use the data in the practice it’s really just a waste of valuable resources (money and time). Think good about what you want to measure and why this measure is importnat in your situation. Knowing your Powerlifters VO2max might be cool, but I doubt that this will help you tremendously to make him perform better in his sport.

This said I found two basic monitoring practices very interesting and helpful for the daily work with athletes, mainly because they are simple, cheap and can help to quick make decisions. They give you a little insight into the status of the athlete; something that is important to manage load and not always is obvious.

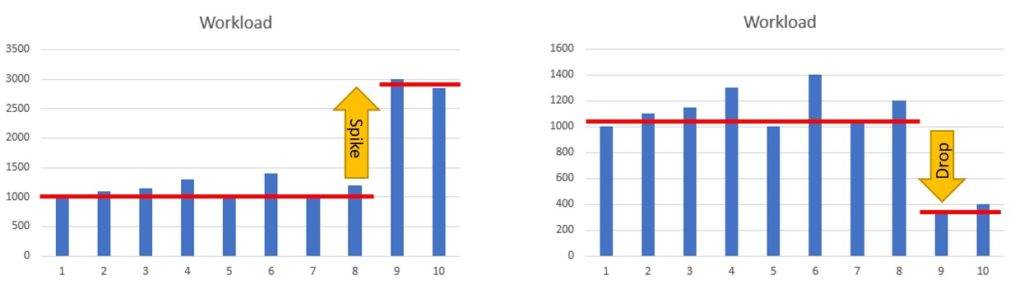

Workload Monitoring with RPE x Duration

As described before, the most basic variables of a single training session are duration and intensity: The duration is easy to measure, it’s just the training length, for the intensity quantification we can use the RPE (Rate of Perceived Effort) where the athlete has to describe on a scale from 1-10 how hard a training session felt. The RPE is a perception value and therefore individual: It can not be compared between different individuals but only with the athlete himself. Other than intensity in %max of some physical variable it is the inner representation of intensity. How can this help us? First, it gives us a feedback if a session we planned to be in a certain intensity range is perceived by the athlete this way. If we plan the session to be light and the athlete’s RPE is a solid 9 we should probably check upon that. Secondly, if we combine duration and RPE of all sessions this gives us an overview of the daily perceived workload of an athlete: With this, we can monitor acute (short-term) with chronic (long-term) workload. I think it’s Tim Gabbett’s work stating, that acute spikes and drops in workload expose athletes to a higher risk of injury due to over- or undertraining. Keeping a somehow consistent training load is important to prevent injuries. I have not gone in depth on his theories, so I might have gotten it wrong, but it sounds pretty logic to me.

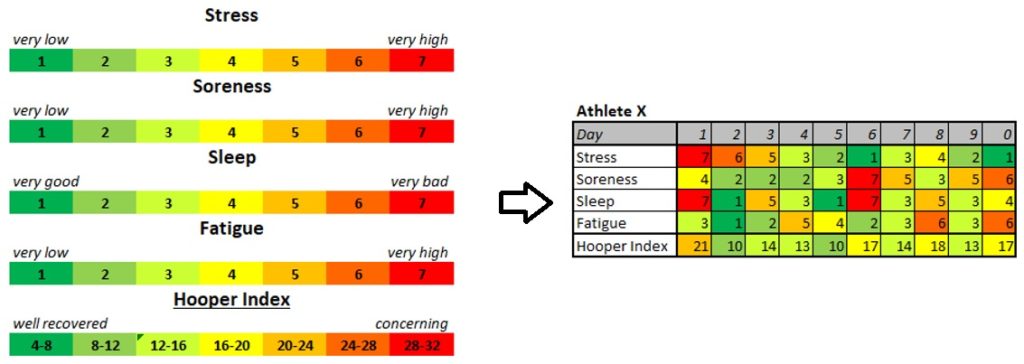

Wellness Questionnaire

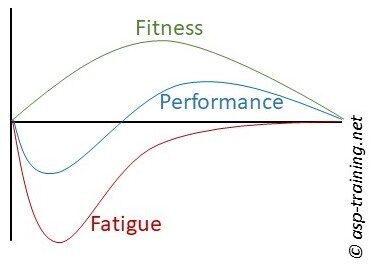

To gather some insight of the status of the sthlete and to estimate where on the Fitness-Fatigue model he currently is, one can use simple questionnaires: Again this is subjective and not comparable between subjects, but gives us a hint how the athlete is feeling and how the different variables changes over time: A widely used way is the Hooper-Mackinnon test or adaptations of it. The variables Stress, Soreness, Sleep and Fatigue are rated on a scale of 1-7 (where 1 is “good” and 7 “bad”) and then combined to a single index variable. It’s simple, free and allows to see acute alarm signs as well as trends over time. One can also extend the wellness questionnaire to more things (nutrition, hydration, pain, etc.) but it is important that the questions don’t take long to fill out. Having a Wellness questionnaire is also a good point to start a conversation with an athlete if we are concerned about single values or trends. (One can consider e.g. using averages vs actual values to find out if things are not “normal”.) Talking with the athletes will always be crucial, you have to know an athlete to make good sense of the data you collect: Stephen Seiler half-jokingly mentioned the “Hair in the cereal test” meaning when an athlete’s head is hanging is in the cereal bowl at breakfast, he might be very tired and need rest and when he’s joking it might be a good day to go. It’s a good reminder to never overlook the obvious signs!

Training is Testing, Testing is Training

If the first part has come off as a rant to modern technology and data collection, it really is not. If it is possible to use data in a good way it will maybe give someone the competitive advantage to optimize the last percent of performance that might make the difference between a silver and a gold medal. I’m also sure that before that happens, we can go a long way with the basics of monitoring. Obviously, I am very interested in what the future brings in means of combining different data sets into a single “master variable” and advancements in algorithms that process the data. This might give coaches a better immediate feedback to make decisions someday, but for now keeping it simple seems to be enough: Where I see great chances to take advantages of the technology advancements is that it is possible to transfer the “lab” to the field or the weight room and include physiological and performance testing in a regular training session. Everything is getting more portable and wireless nowadays which is a great advancement. If we take velocity-based training as an example, we can attach an accelerometer to the bar and see, if the same weight moves faster or slower than the last time and we don’t have to send an athlete to the lab for “testing day”. In general, the possibilities of tracking training have increased, what makes it easier to monitor performance in a realistic setting and more frequently what per se is good. Depending on the sport this can be helpful but it also has its limits: If we take team sports as an example, realistic settings mean chaotic environments: Data that has been taken under different circumstances (e.g. playing against a strong vs weak opponent) cannot been compared 1 to 1 as it is context dependent. Being aware of the limitations, we can still get useful things out of advanced training monitoring in team sports: If we use GPS as an example it makes us possible to see how many high speed sprints have been done by a player which is an interesting measure to quantify performance and intensity.

For Part III I will outline some inputs about load distribution strategies. As in part I and II, I dont consider these information to be something even near to complete. These posts are rather just some inputs that might help other coaches as well. Feedback is always appreciated though.

Alex

PS: Both Workload monitoring with RPE and Wellness questionnaire can easly be set up for free in Google Forms and exported to Excel for processing and interpretation: If you need help with that, just get in touch. I am sure that different apps exist for that as well that are easy to use, so try out and let the other coaches know when you found something good 🙂