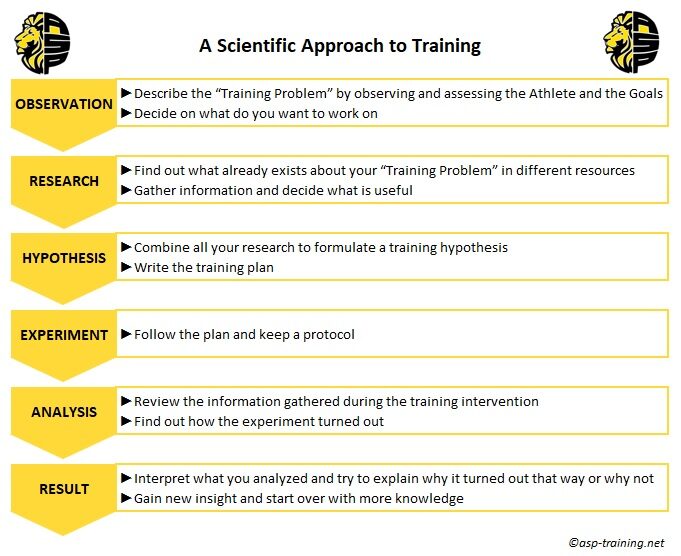

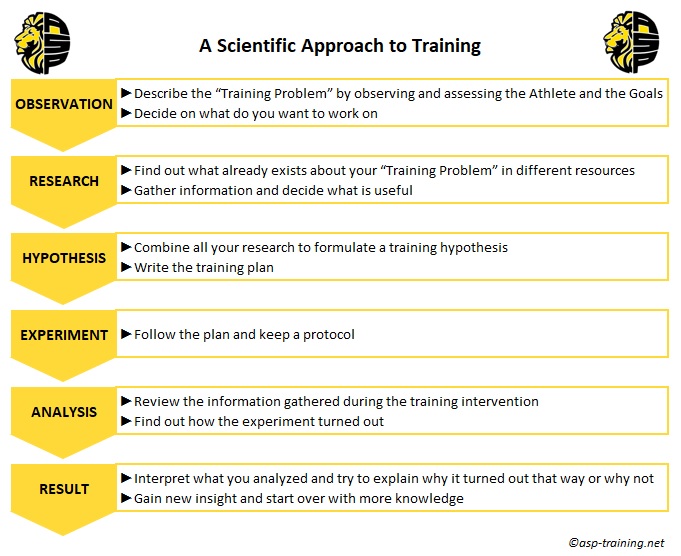

If you ask trainers, what a scientific approach to training means, many will probably start to talk about Meta-Analyses, p-values or new Studies where muscle growth was studied in some special setting showing a huge influence of enzyme XY to angle specific peak force or so and how this is so specific to what whatever (I am exaggerating of course…). While this research is important and might influence what one does in the weight room, it is only one part of the picture: Having a scientific approach, for me, is more than simply base your training on results of “the newest” research. As it already states in the description it is an approach to find a solution to a problem. The human body is an extraordinarily complex organism with numerous interactions that, while helping us to better understand the underlying mechanisms, a single study can never tell us “what to do”. Is this the free pass to weight room anarchy? While smashing burning weights sounds kind of fun, it is not what I mean. If we are humble enough to admit that there is still much to be explored and researched about performance training, we should approach our training as an experiment and using a scientific approach ourselfs instead of thinking we know exactly what goes on. Let me break that what I think a scientific approach is:

1.) Observation

When you start your training phase it is important to find out, where your athlete/client is right now and where he or she “has” to go. Training should start with an evaluation: This can be very in depth with performance testing batteries, analysis of the sport and position, studying training history, watching practices (use the Coaches Eye) and make a complete athlete profile but can also be more simple like asking the athlete and head coach how you can help them. In this step you define the problem you must solve with the athlete or client: The better and more precise you can describe it, the better you can measure if your training intervention successfully solves the problem or not. Let’s assume you have a client that wants to improve his Bench Press: With a weekend warrior this could be that he benches around 90kg and wants to get the Bench up to 100kg because of a bet with a friend. This gives you some direction for the training and with some extra questions you can start the next step. With a powerlifter the observation could more in depth: He might have already a big bench but is struggling with a sticking point or wants to train around a nagging pain to still prepare for a meet. Here you probably need to know more details. It is difficult to say exactly how much you should know and observe, as it is a fine line between knowing enough to act and spending days to analyze the collected information. I personally like to keep it simple to begin with and frequently re-analyze to get a clearer picture. Assessing some objective metrics is never wrong. In the observation step we find out what we want to work on, we formulate the “training problem”.

2.) Research

Once you know what you want to achieve, you can start to dig for information how to solve the problem: Here is where research comes in. Maybe you find studies that explain the problem and offer solutions or ideas, maybe you come up with anecdotal knowledge from coaches in the field, maybe you find something in a book or a blog. You can study the structural anatomy and underlying physiology as well as the biomechanics and the movement models existing. Find out what many coaches agree on being the best practice. You may come up with different sometimes contradicting solutions of how to attack the problem. Make up your own mind, weight the information against each other’s, use logic or seek help at experts etc.… Remember that many roads lead to Rome, at some point you should be pragmatic and start walking. Maybe with your Weekend Warrior Bench Presser you find out that there is strong evidence that muscle cross section area influences strength (there is!) and this could be a way to reach the client’s goal. Then you start to read about hypertrophy methods and decide to work volume dominant to start with, etc. The Research phase focuses on gathering existing information about your “problem”. It will explain the why you will do, what you do.

3.) Hypothesis

After you have done your background research the next step is to formulate a hypothesis: The hypothesis for training is nothing else than the actual training plan. Based on the research you did you can choose the appropriate methods to reach the desirable goal. Here you can play with all the training variables: Exercises, Frequency, Intensities, Volume are only a few parameters and there is an almost infinite amount of combinations. Just don’t forget the why behind what you do and try to keep it somewhat simple. If you change all variables at the same time it will be difficult (impossible) to find out what worked and what not. Optimally you would only change one variable at a time and see what happens. Current “best practices” (= existing methods to solve common training problems) are often a combination of different predefined variables and progression of variables. With your bench client you maybe decide to plan 4×10 Reps of Bench Press with linearly increasing intensity over the weeks as main exercise on a upper body day and work antagonists and synergist as assistance exercises for a 6 Week cycle. The hypothesis explains how you want to solve the problem.

4.) Experiment

Sweat time! Let the athlete follow the plan you created. Oversee the experiment regularly (=coach) so if the experiment would go “wrong” you recognize early and can abort if necessary and reassess. Keep a protocol, so that you can analyze your experiment later and see the planned and the actual training variables. For your bencher as example this could mean that he fills out the training sheet you gave him and every second week you have an “open set” so that you can estimate the 1RM.

5.) Analysis

In Training and Coaching analyzing often goes hand in hand with the training itself as mostly we communicate with the athletes/clients (=feedback). Normally you have a regularly updated picture of the process of the experiment/training. Still after the client finished the full plan you should review the data, maybe repeat test batteries or parts of it and generally do a post-observation. If you have described the problem very precise in the first step, it can be helpful in this phase to detect changes that happend. Could your client keep up with the intensities and volume? Is he moving into the right direction with the bench numbers? How did the Chest circumference change? Did he reach the goal and can bench 100kg? You want to know how the experiment turned out.

6.) Result

Was your hypothesis correct and your training plan worked? If yes, why? What can you use from this experiment for future hypotheses, is there room to further improve? If not, why? Were there confounders like poor nutrition or lack of regeneration? There are many questions you can ask yourself. A result, whether it is negative or positive is a result. In some cases, it might help also to know what does not work for an athlete, so for future you will not use that specific training method. If it worked, keep that knowledge as it might come in handy one day for the same athlete or for future athletes of yours. The Result part is where you interpret what you analyzed and put it into context to ultimately learn more about the athlete and training.

As you see a scientific approach to training for me is more an idea/mindset of how to structure the process of planning a training for an athlete/client. Of course, the research done at labs and new scientific findings help us coaches to formulate a best possible hypothesis, but so does the anecdotal knowledge of coaches that work in the field; just because there is no statistics done and therefore no “significance” does not mean that it can’t be useful. As so often in Training and Coaching athletes it is not black or white but very nuanced.