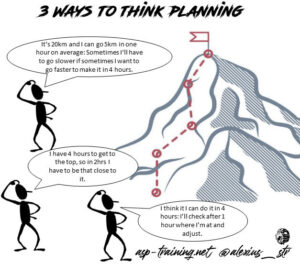

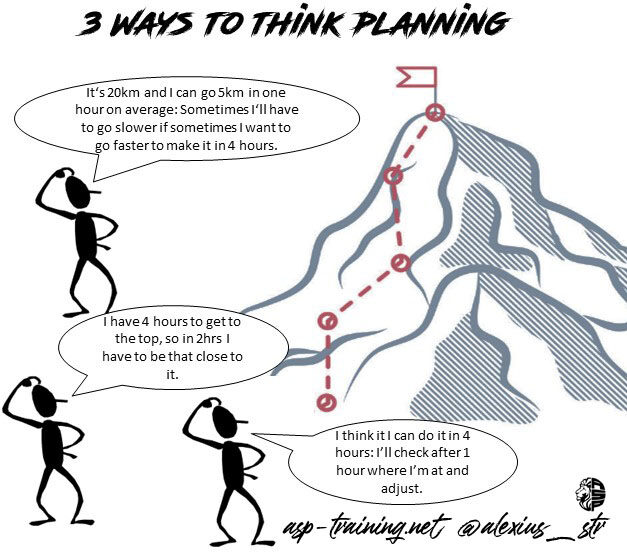

There are different ways of “thinking” when preparing a new training plan (or anything). Most of the time the result will be similar, but the exact result might be slightly different: I have taken three thinking approaches that i’ll quickly present when it comes to strength training planning with a little easy to understand analogy…

Reverse Engineering

I would say planning by reverse engineering is one of the most common and traditional way to approach macrocycle planning. It is very useful, brings results and is therefore very popular. You have the goal in mind which defines your end point, and you start from there. Analyzing your goal and the starting point you divide the macrocycle in different meso- and microcycles depending on how you break down the goal in different subgoals and such. The goal is mostly very specific and if nothing goes wrong you’ll reach it:

It is like when in hiking you know you have 4 hours and want to get to the top: You look at the map and divide the path into different bits like: “To be on the top in time, after 2hrs I’ll have to be there, after 3 there, etc.”

On the pro-side if nothing goes wrong with the execution, your goal is realistic, and you have carefully planned your macrocycle you will most probably reach the goal: On the con-side if any turbulences show up, your meticulous planning is standing on shaky legs.

Agile Periodization

To use the term Mladen Jovanovic popularized, the second approach is very different in thinking even if you end up at the same place in the end. Here you start with where you currently are and a direction where you want to go. From there you plan your first microcycle and reassess after it is done and adapt if necessary: The closer you’re to “the now”, the more precise everything is planned while the more distant planning is vaguer (but existing).

It is like when you hike with the mountain top in front of you and want to get there in around 4 hours: After every hour you check how it is going and what you need to do next to get closer to the top. (Or if would not make sense to seek shelter in a hut when a storm is coming up.)

On the pro-side this approach is more flexible and takes into account that a plan cannot always be executed perfectly. On the con-side the goal, or the timeline, is there, but “foggier” and needs constant revision and adaptation

Capacity Based Approach

A third way is to take the total tolerable training volume as a base and distribute it in a way that it allows you to reach your goal: Of course you have a starting point and a goal, but you center the planning around how much an athlete can actually accomplish and which areas you have to “push” more and in which less. Often you have a limited amount of resources (be it time and or energy) and multiple goals to accomplish so you have to prioritize when you do what.

In a hike it could mean that you know how many km you can do in one hour in general. At some points the terrain will force you to go slower, sometimes you can go faster but overall, you keep your planned “pace” over the whole journey:

On the pro-side it puts an athlete in the center in a way that, before start- and endpoint, the main focus is on what you actually can accomplish. The best plan isn’t working if you can’t stick to it. On the con-side if you guess your capacity wrong you might overshoot the pace and burn out or leave some potential resources unused.

What now?

All approaches are useful and, in my opinion, it needs a little bit of everything to have a successfully working plan: Obviously you need a clear vision where you want to end up and what it needs to get there, so some reverse engineering is necessary. On the other hand, you need to know the capacity of an athlete to set the timeline of a realistic plan. By that you should get the cornerstones which allows you to define the first microcycle. From there obviously you need to reassess often if everything is running according to the reverse engineered plan or if one misjudged capacity or other turbulences show up and the training needs adjustments. It might also happen that the goal itself have to be questioned and changed in the process. As in hikes where a storm may come up, or a path can be blocked by an avalanche, life takes unexpected turns at times and humans are not machines. Even with the “perfect”, evidence based textbook plan you need to be prepared and open to change everything all the time. It’s called coaching and it’s fun!